- Organized by ascending atomic number (# of protons)

- Main Groups (generally collumns): alkali metals, alkaline earth metals, halogens, noble gas, hydrogen

- Blocks: based on number of orbitals

- Atomic size increases down and to the right

- Ionization energy (energy needed to take an electron away): Increases to the right, decreases down

- Metalic character (how easily they allow electrons to flow): decrease to the right, increase down

- Bond polarity: increases up and to the right

- Periodic Table Link 1

- Periodic Table Link 2

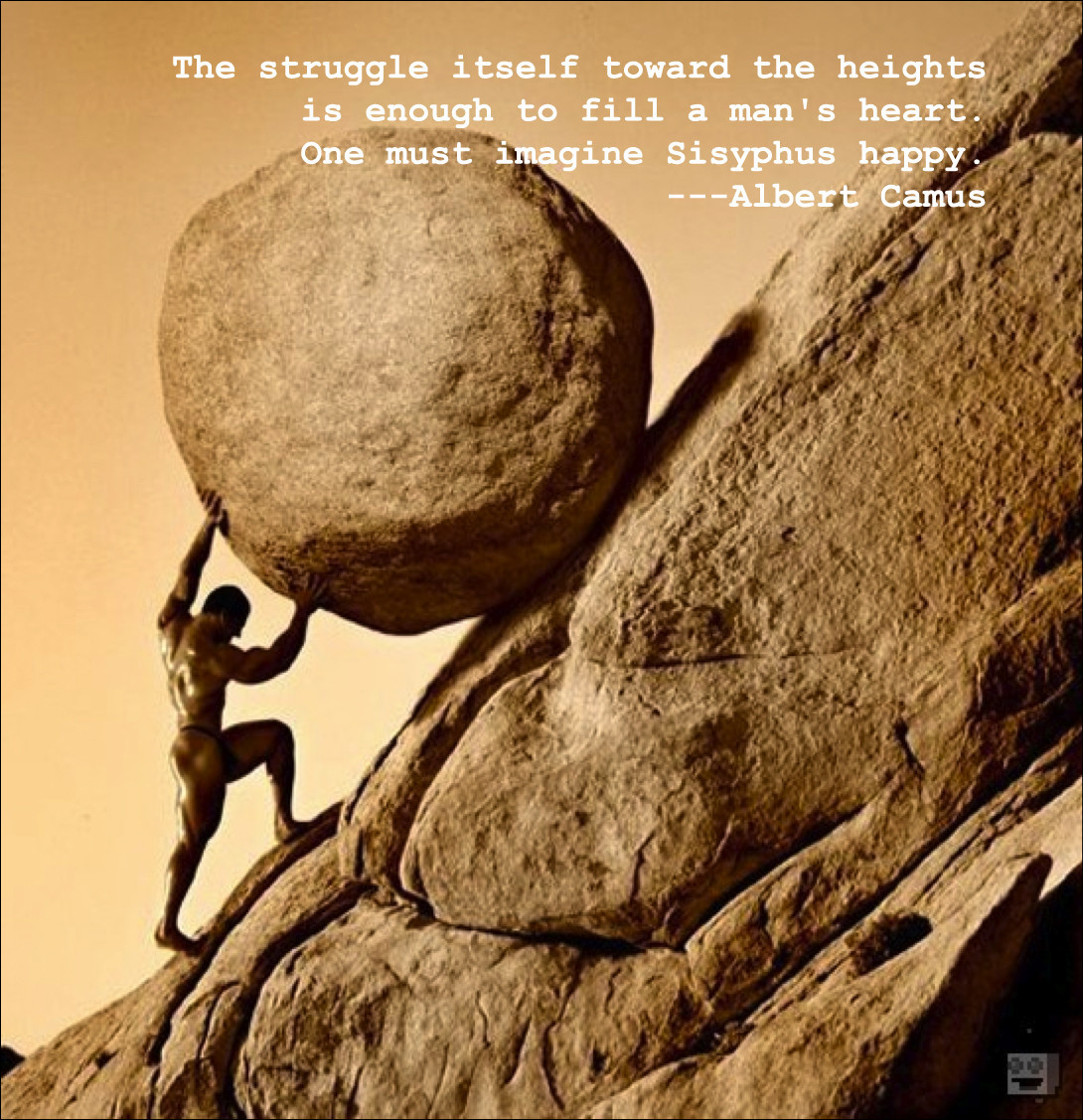

So, as you can see there is/was a great deal of planning and organization involved in the construction of the periodic table. Metaphors can't tell the whole story yet in some ways they tell more than the truth ever could. The ways in which people suffer are certainly connected. Each situation is unique, yet there are common themes and "elements" in them all.

Now to tie things together with the Psychological Suffering course. We have talked in the class about a "optimal" amount of suffering. That is, what amount of suffering keeps enough tension in our lives to allow us to appreciate the moments when we are not suffering. Or, perhaps, there is a certain amount of suffering required to keep "excitement" or "friction" in our lives. In the realm of physics, friction is what allows things to move but it is also a source of resistance. Perhaps suffering is even an essential part of "being human." I wonder, then, if there is a certain essential "deposit" of these elements of suffering in our lives. Do we innately have the propensity for any or all of them to inflamed. At what point does this become crippling or problematic (the same question for "optimal suffering" as well)? For example, it is natural for us to feel anxious about the things that matter to us, like making a life-changing decision. When does that anxiety become inhibiting?

A very wise Algerian Frenchman once said that "The only philosophical question left to answer is suicide." In the Assessment class we also discussed (in a "humanistic" psychology program) if you (the therapist) would lie to your client to keep them from taking their or another life? Of course there are professional ethical standards in place for this, but freely speaking, what if they were not? My answer?.... You bet your *** I would. I don't think that there is a blanket answer to this question though. It is your job as a therapist to assess the situation and take that question in context with the client. The same goes for the "level" of the lie. You don't have to feed them straight nonsense, but you could certainly ease the reality that if there are not hospital rooms available that they may be detained in an isolated prison cell until they can be evaluated. The reason I answered the way I did was quite simple in my mind. Some of my colleagues argued that lying to the client defies the whole concept of being transparent, authentic, and honest with them. Well, you told them the truth. They made up their mind that they were, in no way, going (back to) jail and ultimately do kill themselves. How does your "client-centered" ego feel now that you must live knowing that your professional philosophical prudence meant more to you than another human being's life?

I'll conclude this post with some statistics on suicide in the United States.

- 2010 national rate of suicide = 12.4 / 100,000 (This may not seem like a lot, but in a sport's stadium holding 100,000 people, 12 of them will kill themselves; how's that for perspective?)

- 2010 Deaths by Suicide per day in the United States = 105

- In 2010 Suicide was the 10th leading cause of death in the United States (3rd for ages 15 - 25)

- States with the highest suicide rate (both sexes; most first) = Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico

- States with the lowest suicide rate (both sexes; least first) = New York, Maryland, New Jersey, Rhode Island, Illinois

Follow me on Twitter @Savaged_Zen